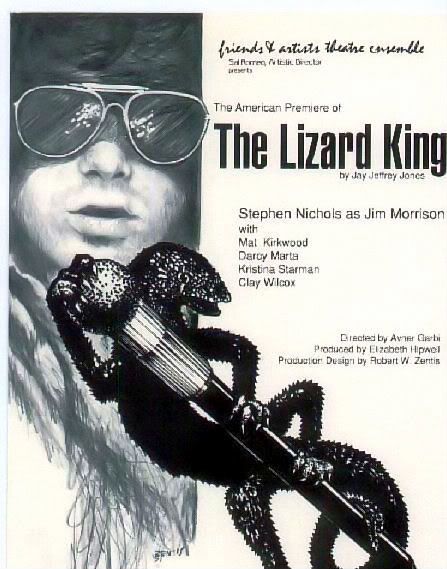

‘The Lizard King’

by Jay Jeffery Jones

Stephen Nichols as Jim Morrison

“It’s 1971, the last 36 hours of Morrison’s life in a Paris apartment shared with his longtime companion Pamela Courson and the ghosts of his incendiary stardom.” – Ray Loynd

Jim Morrison’s Last Words Rock poet’s final struggle to recapture

his artistic vision is at the core of `The Lizard King’

By T.H. McCULLOH

The Los Angeles Times – April 14, 1991

You can lop off a piece of a lizard’s tail, but it will grow right back.

Jim Morrison of the Doors died 20 years ago but, like that lizard’s tail, the vestige of Morrison’s mystical aura returns. Its presence is currently felt in the Oliver Stone film “The Doors,” and opening Friday at Friends & Artists Theatre Ensemble, in Jay Jeffrey Jones’ drama “The Lizard King.”

Make no mistake. This is the play-not the movie. It doesn’t concern the poet-singer’s career, but zooms in on the last 36 hours of his life, in the Paris apartment where he desperately struggled, peering through an alcoholic haze, to recapture his psychic roots and the dream of being a serious poet. It was a dream that had been interrupted by the meteoric rise of the Doors, a vehicle he guided to international stardom.

“From the beginning of his career,” says Stephen Nichols, who plays Morrison in his final hours, “Jim orchestrated the whole thing. He wanted to shake society up. His whole intent was to create this bad boy, lizard king, erotic politician, rock ‘n’ roll god. He knew exactly how to do it.”

Nichols and director Avner Garbi have spent months researching Morrison’s end and the laser-lit life that led him to that Paris apartment. They have dissected Jones’ play, which first saw light in a small Soho theater in London in 1988. “This huge image he’d created for himself became his undoing,” says Nichols. “It was a monster that ate him up. It took away any chance for him to be taken seriously as a poet, and at the same time he had the alcohol working on him. If he could have lasted another five or 10 years and gotten away from the rock ‘n’ roll thing, who knows?”

Garbi first learned of the play when Jones sent it to Hollywood’s West Coast Ensemble, of which Garbi is a member. The WCE schedule was full, so Garbi showed it to Sal Romeo, the artistic director of Friends & Artists, and the opening was set.

Garbi’s first job was finding the right actor to play Morrison. He remembered seeing Nichols in the hit production of a play called “Delirious” in Hollywood.

“That’s where I first saw Stephen,” Garbi says. He thought, “‘That actor was so dangerous.’ Stephen was my first choice.”

Morrison’s character requires that sense of danger, and Nichols’ acting has that quality. When he originally appeared on the soap “Days of Our Lives,” he was cast as a heavy. “I was only supposed to be there a couple of months, but I played the guy real vulnerable, and they liked that. Immediately they had to redeem me. They rewrote things-`No, it didn’t happen that way, this is the way it happened.’ ”

Nichols went on to play Patch Johnson on the soap for five years, and was nominated for an Emmy for his performance. But he’s happy to be back on stage.

“You tend to get stale on a soap and lose sight of where you came from, and why you became an actor,” Nichols says. “Not that you can’t do good work on a soap. I think a lot of the work I did there was fine, and I worked hard. But you really just have to get the hell out and start over and have a regeneration.”

He agrees that TV is not an actor’s medium. “Absolutely not. It’s hard to do anything seriously, because it’s all so quick, and the bottom line is money. It is not creativity. When you’re working on a play, you come from a real focused center as an actor.”

Nichols is emphatic about the fact that he’s not doing an impression of Morrison. He’s trying to find something inside the character that speaks of Morrison’s psyche. Some of that has come intuitively through Morrison’s poetry, much of which was written in Paris, near the end.

“What I first knew about the Doors was pretty much surface, what the media fed me when I was a kid,” Nichols says. “I was 16, 17 years old when the first couple of albums came out, too young to understand the implications of Jim’s music and the poetry within the music. I just listened to the music. Doing the research and finding out what the references in the music were was very fascinating o me.” Morrison’s inspiration came from Baudelaire, Nietzsche and Blake.

“I feel it’s really important to get to the guts of who Jim was and put that on stage, to show the audience his innermost feelings. At first, talking to my wife, I said, `I don’t know if I can do this, if I can do the man justice.’ I didn’t know I would feel that way. I’m a firm believer in the intuitive forces in the universe. Because I’m working hard and doing research, I think I’m getting tuned in to his spirit. He’s not coming to me in my dreams and talking to me, but his words speak to me.

“About two months ago I was reading some of his poetry from the last book that just came out, `Wilderness, Vol. 1,’ and in it was the poem `Road Days.’ When I read that I felt he was saying, `Stephen, you can do this, you have my permission.’ I’m not saying he came to me in a vision, don’t get me wrong. This is my own intuitive feeling.”

It’s a feeling Morrison’s poetry creates, and some of that quality transfers into the text of the play.

“One of the wonderful things Jay Jones captured,” says Garbi, “he based a lot on Jim’s poetry. He took from the poetry the feelings of what happened in that apartment in Paris. If you read the poetry, a lot of the play reflects Morrison’s pain. He wrote the bulk of his major work in Paris, the three or four months he was there. Jones based the scenes in Paris on that. In the play you see his tormented soul, his tormented mind questioning what really brought him to what he was. He had a very sad life.”

Nichols adds, “Very few people have tried to speculate where Morrison was at, and how he was feeling in Paris, what his attitudes were about what had happened to him in the previous years. Nobody has really gotten into that can of worms.”

“The Lizard King” attempts that kind of speculation, putting a magnifying glass on a natural phenomenon called Jim Morrison, looking for missing pieces like the tail of that elusive lizard. It’s the kind of puzzle that fascinates the director, Garbi, and Nichols, the actor who is trying to fit together what is left of Jim Morrison in his poetry.

“I know why I’m doing the play,” says Nichols. “I’m doing it because it’s an enormous challenge for me as an actor, the greatest challenge I’ve ever had, and I’ve been around for almost 20 years. Here we are, in this little 48-seat theater, and,” he continues, pointing to the set, “that’s my room in Paris over there, and I’m thrilled. It’s what the doctor ordered for me.”

`The Lizard King’ Documents Jim Morrison’s Final Hours

By RAY LOYND

Los Angeles Times – May 29, 1991

The music’s over for Jim Morrison. He’s bloated and boozy but still the dangerous poet, spilling his invective into a tape recorder between drinks and just before oblivion.

It’s 1971, the last 36 hours of Morrison’s life in a Paris apartment shared with his longtime companion Pamela Courson and the ghosts of his incendiary stardom.

The American premiere of playwright Jay Jeffrey Jones’ “The Lizard King” at Hollywood’s Friends and Artists Theatre cannot be compared with Oliver Stone’s “Doors” movie-the play is telescoped and downbeat whereas the movie is an epic-sized rock ‘n’ roll celebration. But, interestingly for Doors and Morrison fans, an uncanny continuity connects Val Kilmer’s screen performance and Stephen Nichols’ stage-bound lizard king.

Needless to say, Nichols’ Morrison is a tougher act. He’s no sexual glamour boy. With Byron, Shelley and Keats, the myth of dying young was at least romantic. Here the self-exiled Morrison and would-be writer is too burned out and drunk to sing, to make love or face up to responsibilities. That’s not to say he can’t still lyricize.

This is not a musical (Martin Allen Davich’s original background score notwithstanding). It’s a horror story and a fascinating coda to the Morrison legend and a play buttressed by the playwright’s interviews with Morrison’s drinking buddy, the late porn actor Tom Baker (capably played by Clay Wilcox).

This American premiere of a drama that opened in London three years ago seems a catch for a small house like Friends and Artists. The narrow theater may have the hardest seats in town but director Avner Garbi, a talented five-member cast and an artful design team led by set designer Robert W. Zentis lurch you into another world.

Let’s face it-the death of a rock star is not exactly fresh territory, especially a drama as assaultive as this one. But Nichols’ heavily bearded, black T-shirted figure and his stream-of-consciousness rantings are laced with humor and never boring. Nichols is an actor absorbed by his character.

For example, the king’s sexual impotency, in the show’s most daring moment with raven-haired Kristina Starman as the overwrought lover Pamela, is risky but dramatically potent. It underscores the tone of decay and desperation.

Emblematic of the precise staging is a beautiful scene in which Morrison and his flustered manager Max (Mat Kirkwood) argue on one side of the stage while two women (Darcy Marta’s Edie Sedgewick character and Kristina Starman’s Pamela) sniff coke and wordlessly cuddle and giggle on the other side.

At the end, Morrison is going to get things back together. Maybe even move back to L.A. He and Pamela patch things up for the night. He’ll see her shortly. First he’s going to have a little drink and prepare a bath. He sits down by his tape deck and the house lights narrow to a single light on a revolving audio cassette.

Click Here for a Viewer’s Personal Review of ‘The Lizard King’

no comments